High-rises under construction in the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone.

Businessweek | The Big Take

A Chinese businessman persuaded officials to establish a special economic zone in a remote part of Laos. The gamblers arrived first. Then came the drug runners and human traffickers.

The Golden Triangle, the mountainous region where the borders of Laos, Myanmar and Thailand meet, is wild and remote, distant in every sense of the word from the centers of all three countries. Away from the few towns, settlement gives way to small plantations of coffee and bananas and then to thick, steeply graded forest. The main thoroughfare is the Mekong, the silty river that runs from the Tibetan Plateau across Indochina all the way to tropical southern Vietnam.

It’s startling, then, to descend a winding road from the highlands and suddenly see skyscrapers, shopping areas, a casino and an artificial lake, dropped as though by magic onto the Laotian side of the river. Just down the bank, cranes hover over another crop of towers that are advancing toward completion. After dark, thumping electronic beats from buildings illuminated with dancing spotlights and neon accents can be heard across the Mekong in Thailand.

This is the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, a vast development project founded by a Chinese businessman named Zhao Wei. Outwardly it resembles a midsize Chinese city; it even has an airport, with a soaring terminal that Zhao hopes will eventually welcome international flights. In interviews and on Chinese social media, he’s said one of his top priorities is to help the Lao people, who are among the poorest in Southeast Asia, “and to provide a bigger contribution to the country’s economic and social development.”

Where Is the GTSEZ?

Behind the glassy facades, however, more is going on. The GTSEZ operates as a self-governed enclave, and for the better part of a decade investigators have warned that it’s a hub for criminal activity of every description—a legal no-man’s land. At first, according to the US Department of the Treasury and other agencies that have examined the zone, one of its main businesses was drug trafficking, particularly of methamphetamines. They’re often mixed with caffeine to create cheap pills called yaba or else refined into pricier crystal meth and exported to wealthy countries.

More recently, the GTSEZ has diversified into hosting “scam centers,” where teams of operators, many of them victims of human trafficking, persuade online marks to move their savings into fraudulent crypto-trading schemes. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and other agencies have identified the GTSEZ as a nexus of money laundering as well, connecting criminal groups from Taiwan to Myanmar that use crypto, underground casinos and shadow banking to move ill-gotten gains. “It’s a multifunctional criminal enterprise,” says Richard Horsey, a senior adviser to the International Crisis Group who has studied the zone. “The GTSEZ business model is to provide the infrastructure. They create that ecosystem so that criminal businesses can come in, lease the premises they need, hire the armed security they need and get whatever they want.”

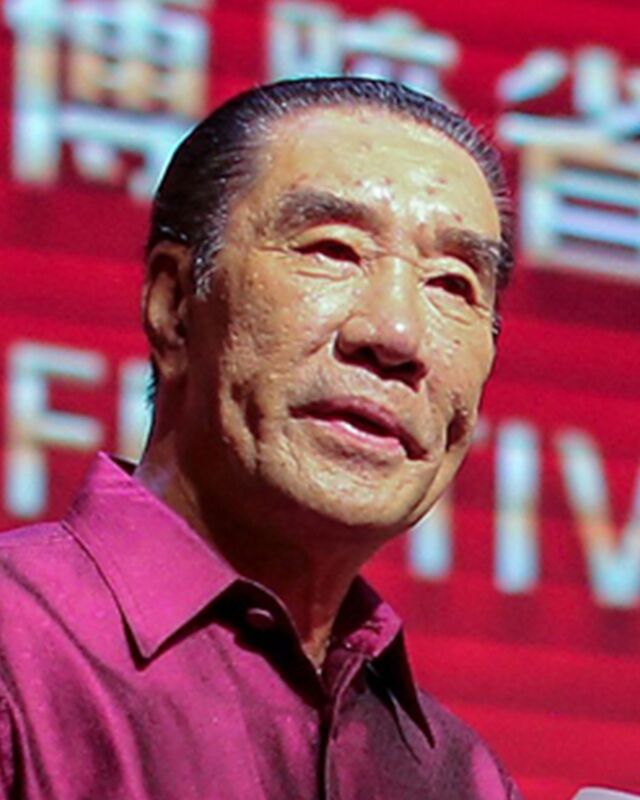

Zhao Photographer: Pongmanat Tasiri/SOPA Images/Shutterstock

The GTSEZ’s management didn’t respond to a detailed request for comment from Zhao. He’s said in the past that drugs and drug trafficking are prohibited in the zone and that “we definitely do not allow scamming” or human trafficking. Suggestions that he’s involved in criminal enterprise, he told Thai media last year, stem from “the issue of the US trying to contain China.” He hasn’t been charged with any crime.

Even as the GTSEZ grows in plain sight, law enforcement agencies can do practically nothing to police it. In 2018 the Treasury Department imposed sanctions on what it called the Zhao Wei Transnational Criminal Organization, which it said engages in “drug trafficking, human trafficking, money laundering, bribery, and wildlife trafficking.” But those sanctions have had no obvious impact on the GTSEZ’s expansion. Moreover, any move by the US or another country to initiate a prosecution would be complicated by the apparent disinterest of Laos’ leaders, who’ve never taken action against Zhao. In fact, the nominally socialist Laotian government, which has close ties to China, is one of his business partners: The state received a 20% stake in the GTSEZ after he was granted the right to develop it in 2007.

Laotian officials didn’t respond to requests for comment on this story. After Bloomberg Businessweek sent its inquiries, state media reported that the government had ordered the removal of scam centers in the GTSEZ by late August. It’s not clear how, or whether, such an order would be enforced.

For now, Zhao is likely to continue running an unprecedented entrepreneurial experiment. Organized-crime groups have long sought to influence and profit from how cities are run. In a few exceptional cases, such as Naples in the heyday of the Camorra and the alliance in New York between Tammany Hall and the Mafia, they’ve managed to insert themselves into government, at least for a time. But the allegations against Zhao describe a much more ambitious endeavor: to create a vertically integrated paradise for criminal activity, from scratch. And according to investigators, it’s paying off.

Watch: Inside the Dark World of Asia’s Golden Triangle

Among entities that the US government designates as criminal organizations, it’s likely that only Zhao’s enterprise publishes a thick brochure for prospective investors. In addition to boasts about “diversified industrial structure, abundant human resources and public service facilities,” it lays out some of his future plans for the GTSEZ. These entail dramatic expansion, partly through facilities such as an “E-cigarette Industry Base” and a “Big Health Medical Industrial Park.” The document envisions a city of 300,000 residents by 2026, up from perhaps tens of thousands now. That would make the GTSEZ easily the second-largest urban center in Laos after the capital, Vientiane.

Development on this scale is a long way from its founder’s origins in Baiquan, a poor, windswept county in China’s northern Heilongjiang province. Zhao, who’s slim, with slicked-back hair and bushy eyebrows, has said that he left school by the age of 12; after that he did farm work and eventually became a timber trader. In the 1990s he relocated to Macau, Asia’s gambling capital, and entered the casino business. The territory was booming, and not only because gambling is officially illegal in mainland China.

To protect the value of the yuan and stop citizens from moving large amounts of money overseas, China imposes strict controls on international financial transfers. For decades, one of the easier ways to circumvent the rules was with the help of organizations known as junkets, which provide credit in casinos outside China but collect on the debts domestically. After being washed through Macau’s gaming tables, the money—some of it the proceeds of corruption or other criminality—could be cleanly deposited into foreign banks.

But Macau was a crowded market, and Zhao eventually relocated to the much smaller gambling center of Mongla, along the Chinese border in Myanmar’s Shan State. That move didn’t pan out, either. The target customers in Mongla clearly weren’t citizens of Myanmar, which has a per capita gross domestic product of about $1,200, and the Chinese government eventually cracked down, heavily restricting border crossings. By 2005 it had destroyed the local casino industry.

Zhao moved again, this time to Laos, inside the Golden Triangle, which has long been a shelter for criminal activity. Some of the first to take advantage of its potential were former generals of the Kuomintang, the nationalist Chinese government that Mao Zedong defeated in 1949, who relocated to Myanmar and set themselves up in the opium trade. They were followed by other drug kingpins with connections to the ethnic militias that operate in Myanmar’s restive border regions and fund their operations through narcotics. (A spokesman for the military junta that governs Myanmar said it “considers anti-narcotics operations as a national duty.”)

Chiang Saen at lower left, facing the GTSEZ across the Mekong.

In 2007 the Laotian government, hungry for investment, agreed to create the GTSEZ, granting Zhao, who’d developed close relationships with decision-makers in Vientiane, a 99-year lease on a swath of little-developed land. The use of the term “special economic zone” harked back to China’s own economic transformation, when Deng Xiaoping designated Shenzhen, then a modest regional center, as an area where many Communist Party regulations would be relaxed. Zhao’s arrangement essentially made him the sovereign ruler of 39 square miles of rural Laos. To clear land for construction, the government relocated residents. Laws would be written by Zhao and his associates, and a private security force would maintain order. Laotian police could enter only with his forbearance.

Zhao set about building what amounted to a small city, starting with a gambling palace he called the Kings Romans Casino. To handle the construction, says a person familiar with the process who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation, Zhao hired Burmese laborers who were willing to work for only $5 or $6 per day and live in shanties on the outskirts of the complex. Once the casinos and surrounding businesses were up and running, they were staffed largely by Chinese migrants, serving crowds of Chinese visitors. Mandarin was the lingua franca, and the yuan was the currency used in most transactions.

Zhao was on his way to becoming a powerful figure. Then, four years after he started work on the GTSEZ, an unexpected chain of events gave him even more influence over his stretch of the Mekong. In October 2011 unknown assailants raided two Chinese cargo ships on the river, killing 13 sailors. A vast manhunt culminated in the arrest of Naw Kham, one of the region’s most notorious warlords. Extradited to China’s Yunnan province, Kham was convicted of planning the attacks and executed, along with three associates.

Regional security experts have suspected ever since that Kham wasn’t the true culprit and that Beijing used the murdered sailors as a pretext to eliminate a troublesome criminal. Either way, his demise left Zhao as the dominant player in the Golden Triangle. It didn’t take long for law enforcement agencies to suspect that casino tourism wasn’t his sole business. In particular, according to a former police official who asked not to be identified discussing nonpublic information, they were receiving reports about methamphetamine shipments moving through the GTSEZ.

Investigators determined that at least some of those drugs came from the United Wa State Army, a secretive military force that dominates parts of Myanmar. In the areas they control, the Wa function as a government, with a flag, a national anthem and as many as 30,000 men under arms. Drug trafficking is their main source of revenue. The US government designated the UWSA as a “drug kingpin” organization in 2003; two years later federal prosecutors indicted eight of its leaders on heroin and methamphetamine trafficking charges. (None was successfully extradited.) Tellingly, when the US targeted Zhao with sanctions in 2018, one of the listed companies, Kings Romans International (HK) Co., was registered to the same Hong Kong address as a previously sanctioned Wa-linked company.

Although the 2018 sanctions barred companies and banks from dealing with Zhao, he evidently found alternative sources of financing. The GTSEZ continued expanding through the Covid-19 pandemic, with investigators suspicious that many of its elaborate development projects were being used to launder the gains of drug sales—for example, by using a friendly contractor to overbill for services, with the excess payment becoming the revenue of a nominally clean enterprise.

Beginning around 2022, police and diplomats in Southeast Asia took note of what appeared to be a major new business in the GTSEZ: the crypto scam centers. Much of the information about them came from workers who said they’d been lured to Laos on false pretenses and then held in the complex against their will before somehow securing their freedom. They hailed from a remarkable range of countries, from Brazil to Indonesia.

Similar stories were playing out in other scam hubs in Southeast Asia, notably in Sihanoukville, a Chinese-dominated city in Cambodia. For governments in the region and elsewhere, the operations have become hard to ignore, and not only because of the harrowing accounts of trafficked workers. In a report published in May, the US Institute of Peace (USIP), a Congress-funded research institution, estimated that the amount stolen by scam centers in the Mekong countries “likely exceeds $43.8 billion a year.” That total includes considerable losses in China, as well as the US and Europe.

There’s evidence that Chinese policymakers, who wield enormous influence over Laos, want to see the frauds reined in. In recent months, Laotian authorities, presumably at the Chinese government’s urging, have arrested more than 1,000 Chinese citizens in raids of scam operations in the GTSEZ and deported them to their home country. The actions showed that it’s possible, at least when China applies the necessary leverage, for police to enter the GTSEZ and make arrests. But there’s no evidence the threat has slowed down Zhao.

At a ferry terminal in Chiang Saen, the small Thai town directly opposite the GTSEZ, signs warn passengers of what might await them on the other side of the Mekong. “Don’t believe persuasive words that promise high compensation,” says one, illustrated with a cartoon police officer pointing his index finger at passersby. “You will become victims of forced labor and detention.” Chiang Saen residents say they often encounter groups of young people from a multitude of countries toting luggage for long stays, heading for the ferry in the company of unsmiling handlers. One local recalls warning some of them and receiving an angry response from their chaperones.

At first glance during a recent visit, little about Zhao’s city looked particularly sinister. There were no obvious restrictions on who could enter. The roads were wide, clean and smooth, lined with palm trees and carefully pruned plantings. In a lush park, workers lounged in the shade with their phones not far from a startling public-art installation: a sculpture of an “Anti-Drug Goddess,” a sleeping woman who appeared to have just emerged from underground. Nearby, vendors hawked coffee and street food with prices listed in yuan. One said that Zhao set the prices, with stall operators required to purchase supplies such as bottled water from him and his associates. The area feels like “their country, not ours,” said a young woman nearby. (The Laotian government is highly repressive, and speaking to journalists can lead to severe consequences. As a result, Businessweek is protecting the identity of Laotian citizens cited in this story.)

The busiest area was around the flagship casino, a fauxclassical pile topped with a golden crown that would give pause to an in-house architect at the Trump Organization. Hundreds of motorbikes were parked outside, overseen by vaguely Greek statues. The din of construction was everywhere, as workers hammered away at perhaps a dozen high-rises. They’ll surround a new open-air shopping complex, featuring a Disney-style castle. Inside the casino were tables for baccarat, a card game favored by Chinese gamblers. A separate section was dominated by Thai day-trippers, mostly older men and women playing for small stakes. Afterward gamblers might wander into “Chinatown,” an adjacent shopping district with ample food options, including what appeared to be a knockoff KFC.

Bokeo International Airport.

Reaching Zhao’s most ambitious project, Bokeo International Airport, required leaving the GTSEZ through a security checkpoint and entering rural Laos. The contrast was jarring. Reddish dust clouded the air, hanging over dead trees and rocks broken down for construction. Bone-thin cattle ambled by the roads, trying to feed on sparse patches of grass.

After a short drive, a Zhao-built golf course came into view and, beyond that, the airport. Named for the Laotian province that surrounds the GTSEZ, Bokeo International opened earlier this year, in a ceremony attended by Zhao and Prime Minister Sonexay Siphandone. The terminal is comically oversize for current traffic levels. A staff member said there were only two flights a day, both from Vientiane, and passengers barely outnumbered security officers, who patrolled floors polished to such a high sheen that visitors could see their reflection.

Despite the brochure-ready gleam of Zhao’s empire, other corners back in town hinted at the illicit activities law enforcement officials say are rife. Near the casino, in the center of the GTSEZ, stood a number of tall, unmarked buildings without balconies. One was surrounded by a fence topped with barbed wire. Another had an air-conditioning compressor next to nearly every window on the upper floors, suggesting they’d been divided into many small units. Almost all these windows were boxed in by metal cages, their bars so tightly spaced it would be hard even to pass one’s arm through. There were clothes hanging from the metal—evidence that people lived inside.

Barred windows in the GTSEZ.

About two years ago, Siti, a young Indonesian woman, answered an intriguing job ad on Facebook. (Her name has been changed to protect her from retaliation.) She says a recruiter told her that the role, based in Thailand, would involve working on graphics for new online games, which matched well with her skills. The salary was a generous $1,500 a month, with costs for flights and work permits covered.

Following the recruiter’s instructions, Siti flew in July 2022 to Chiang Rai, in northern Thailand. A driver picked her up and brought her to the ferry docks in Chiang Saen. She didn’t realize she’d be crossing into another country until a border agent asked for her passport. After traversing the Mekong, she was taken to an apartment building in the GTSEZ.

There, Siti says, a manager told her and other recent arrivals that they’d be working as online scammers, not graphic designers, and that if they wanted to leave, they’d have to pay back more than $5,000 in supposed travel and visa costs, an impossible sum. Escape wasn’t an option. Siti says that she had to surrender her passport and that exiting the building required an access card she didn’t have. She was allowed to keep her phone, but her managers would regularly go through her messages.

Siti was shown to the small bedroom she’d be sharing with several other women. Then she began learning the contours of her new job: She’d be hanging out on dating apps, most commonly Badoo, and making contact with Americans, posing as an Indian woman who’d recently moved to Virginia. To align with US time zones, she arrived at her desk as late as midnight and worked until noon or 1 p.m. The $1,500 monthly salary was a mirage; in fact, she says, she received no pay.

The scams were a classic example of “pig butchering,” in which fraudsters slowly build a relationship with the marks—fattening the pig, to follow the metaphor—before persuading them to part with as much cash as possible. Siti says she would gradually hint that she’d been successful with investing, and if her mark expressed persistent interest she’d get him to place money through her. The trades would generate real profits at first. Then, when her managers said it was time, she would try to persuade the American to put down all he could afford—money that would disappear. “The customers are looking for friends, so I think they’re very fast to trust,” Siti says.

She hated the work but saw no alternative. Workers who failed to find “customers” were punished. Siti says she saw one man being beaten with a leather whip so severely that his blood ran across the floor. Others were locked in rooms without food. (Two other Indonesians who worked in the GTSEZ told Businessweek they went hungry for a week after demanding to go home. Another said he was hit with sticks when he fell short of his revenue target.)

Siti saw her chance to flee about two months after her arrival, when she was given her passport and told to return to Chiang Saen for a new entry visa. Back on the Thai side of the border, she says she waited for a moment when no one seemed to be watching and took off on foot. Eventually she found a taxi driver willing to bring her to the Chiang Rai airport for the small amount of money she had left. Fearful of being caught even then, Siti says she crouched behind the counter in a SIM card shop awaiting a flight to Bangkok. A friend bought her the ticket online.

The money from operations such as the one Siti says she endured is thought to go mainly to the many small companies renting space in the GTSEZ to run scams. But investigators say it’s almost certain that Zhao, as the landlord and facilitator of their activities, gets a cut. It’s impossible to know how many people are being held against their will, but USIP, the Congress-funded research group, estimates there could be 85,000 in Laos alone, with the majority likely in the GTSEZ.

Siti says she found it bewildering to be in a place that appeared to be beyond the reach of any law: “I was asking my boss, my manager, ‘Why police cannot come inside the building?’ And he told me, ‘This building, this area, it’s the personal area of the big boss.’ ” The “big boss,” the manager informed her, had a 99-year lease.

The Thai soldiers set out in the late afternoon. After clapping magazines into their assault rifles, seven of them filed out from their post—a clutch of buildings, fenced with sharpened bamboo stakes, on a high ridge marking the Thai-Myanmar border—and hopped one by one over an irrigation ditch. The ground fell away, and soon they were marching across a steep hillside facing Burmese territory, digging their boots into the soil for traction. Smoke hung in the air from distant fires downslope. At intervals, the squad’s commander signaled a stop, and they dispersed, crouching down among rows of coffee plants and scanning the horizon for danger.

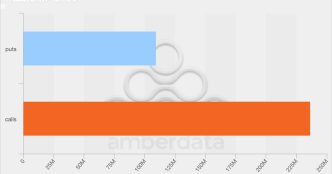

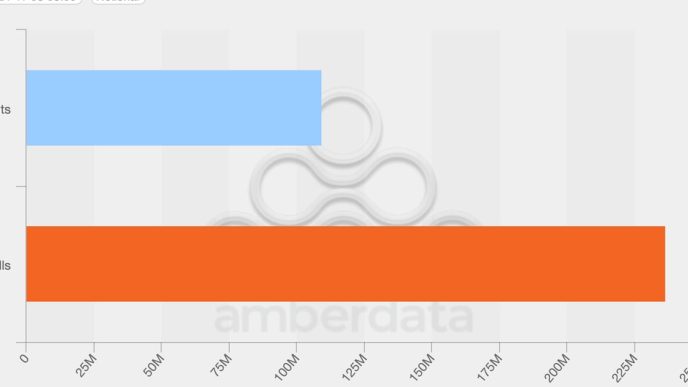

The Royal Thai Army runs these patrols constantly along the nation’s northern borders. The expeditions can be perilous. Only two days earlier, a squad had encountered a half-dozen drug couriers moving methamphetamine into Thailand. The couriers began shooting, and the soldiers returned fire. The couriers scattered, dropping their cargo behind them. The Thais recovered 480,000 yaba tablets—a medium-size haul, by current standards. Between December 2023 and July 2024, Major General Nirunchai Tipkanjanakul explains, the authorities intercepted more than 200 million yaba pills in the region.

The narcotics exported through the Golden Triangle, many of them en route to Thai seaports, come from a number of sources. But the GTSEZ appears to play a significant role in the distribution network. It’s “more than a safe haven,” says Commander Paula Hudson, who manages transnational operations for the Australian Federal Police. “It’s an enclave for drugs—for transshipment, safe storage, where they can be stored and packaged up and then moved around the globe.” Another international law enforcement official, who asked not to be identified because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly, likens the GTSEZ to a tollbooth. If traffickers moving shipments through Zhao’s area of operations fail to employ its services or pay a fee, the official says, they might find their cargoes seized by authorities who’ve received a conveniently timed tip. This result can be particularly true for consignments moved by boat down the Mekong, which pass directly in front of the GTSEZ’s own river port.

Police throughout Southeast Asia are eager to move against the complex, even as they concede that drug operations and scam centers could easily shift elsewhere, perhaps into parts of Myanmar that are still further beyond the reach of law enforcement. But there are huge practical problems, starting with the reality that the Laotian government, a shareholder in the GTSEZ, has in the past demonstrated little ambition to regulate Zhao’s activities. After the US sanctions, Laos “took no action” to respond, according to a 2023 report by the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering, a multilateral compliance body. The Laotian financial system has weak anti-money-laundering controls, the report noted, and the GTSEZ has “no measures to prevent criminals or associates from holding a significant or controlling interest or management function” in financial institutions. And whether its purported crackdown on scam centers amounts to anything remains to be seen.

Without Laotian cooperation, charges against Zhao or his associates would have to come from another country—probably the US. But US Attorneys’ Offices don’t often bring charges when there’s no realistic hope of arresting the defendant. And Zhao, law enforcement officials say, rarely if ever travels to countries that might act on an American request to detain him. Even if he were captured in such a place, he might find a way out. After a suspect in the federal investigation of drug trafficking by the Wa, Ho Chun Ting, was arrested on US charges in Hong Kong in 2007, he was released without explanation before he could be extradited.

A hotel pool in the GTSEZ.

Looming over all of this activity is the question of what China, the one major power that certainly could constrain the GTSEZ’s operations, makes of it. The Chinese government has sought for decades to build influence in the nations along the Mekong—emerging economies with a combined population of about 250 million and ample natural resources. But Zhao’s complex isn’t part of the “Belt and Road” initiative, President Xi Jinping’s ambitious plan to develop infrastructure and commercial links across the developing world, and Zhao has no formal relationship with the Chinese state. He nonetheless presents his activities as aligned with Chinese policy. In an interview last year with Laotian media, he said the GTSEZ will “create a foundation where the two countries can have commercial and economic exchanges.” (China’s foreign ministry didn’t comment specifically on the zone but said the country always works with neighbors to combat transnational crime and protect border security.)

Even if China disapproves of activities such as running scam centers, it may consider Zhao an asset in a strategically important area, says Kelley Currie, a former US diplomat who’s now a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington. In the Golden Triangle, the Communist Party has “at various times instrumentalized these groups when it’s convenient to them,” Currie says. “But they’ll also disavow them or make arrests or even execute their leaders if they have to.”

When the GTSEZ was first being built, Laotian authorities forced local residents—mostly rice and corn farmers, who’d worked the area’s high-quality alluvial soil for generations—to relocate, with modest compensation. Although the residents were initially told the development would bring economic opportunities, relatively few found employment there. Construction jobs went to the Burmese workers whom Zhao had hired; roles in the Kings Romans Casino, hotels or other service businesses required competency in Chinese, which few of the villagers could speak. Today, some do odd jobs or work as drivers. Others scratch out a living by farming the tiny plots of land around the homes they were moved into.

At one resettlement site not far from the border of the GTSEZ stood rows of detached two-story houses, each painted white and with a small front porch. Outside one, a woman in her 30s explained that she once farmed an area now occupied by an entrance checkpoint. When the government told residents to move to make way for Zhao, “there was just no choice,” she said. Another resettled woman, visiting from a different community, said she missed her old way of life: “It’s not fair, but we can’t say anything.”

The women said they and their neighbors had tried to make the best of their situation. But since being displaced, they’d witnessed the GTSEZ expand continually, its footprint growing to several times its initial size. Even as they spoke, construction continued nearby. They said they worried that soon someone would appear at their doors, telling them once again that Zhao needed their land. —With Regif Asri Ibrahim, Annie Lee and Khine Lin Kyaw

More On Bloomberg

Source link

Matthew Campbell

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2024-golden-triangle-special-economic-zone/

2024-08-20 00:00:00